World Gorilla Day: Will better public health save Uganda’s gorillas?

Meet Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka, Founder of Conservation Through Public Health. Gladys works tirelessly to protect gorillas in Uganda from catching human diseases spread through tourism and the use of gorilla ‘scarecrows’ by local communities — and last year I was fortunate enough to have the opportunity to interview Gladys on behalf of National Geographic Kids magazine via the Whitley Awards.

Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka, Uganda’s first wildlife vet, told me about her work to save gorillas by stopping the spread of diseases between the great apes and humans.

She began her career as a Veterinarian after training at the Veterinary Medicine University of London Royal Veterinary College, before founding Conservation Through Public Health; which monitors and tracks diseases spread between wildlife, humans and livestock to prevent major outbreaks.

Kate: Hi Gladys, it’s wonderful to meet you. Have you always loved animals?

Yes. I always wanted to be a vet when I grew up. I started a wildlife club in my high school in Uganda, which is where I heard that there were mountain gorillas in my country. At that time the gorillas were not a part of tourism or research, so you couldn’t go and see them – but I really wanted to see them!

What was it that made you so interested in the mountain gorillas?

They are very gentle; like gentle giants. And they are very similar to humans. They’re very intelligent – when you look them in the eye, you feel like you’re really connecting with them.

Was it your love of gorillas that made you become a wildlife vet?

At first I wanted to be a vet working on all animals, but later, I attended the Royal Veterinary College at the University of London, and my first study was on chimps.

It was chimpanzees and not gorilla, because people were still not allowed to be in contact with the gorillas, even then. Two years later, in 1994, I finally got to see and study the gorillas in Uganda and ever since then, I knew I wanted to work with them for the rest of my life. After I was working with the gorillas, I specifically wanted to be a wildlife vet.

I eventually ended up setting up the Vet Department of the Uganda Wildlife Authority.

How exciting! So, did you expect to work with lots of different wildlife when you became a vet, or just the gorillas?

Well, the Ugandan Wildlife Authority hired me because they felt they needed a vet to stop the tourists giving the gorillas diseases, and they’d never had a vet before – in the whole wildlife department!

So of course when I started they got me to do many other things to – “this elephant is sick… move these giraffes… move this… move that…”. They wanted me to help with every species of animal in the area that needed vet care.

Luckily, when you’re a vet you train to work with all different animals, but it was still a very steep learning curve. But it was fun, because I got to work with other vets with more experience in looking after different animals, I got to learn lots from them.

What is it that you do in your daily job with mountain gorillas?

I started the organisation ‘Conservation Through Public Health’, which helps gorillas and the local community to live side-by-side successfully.

The big problem is that gorillas share approximately 98% of their DNA with humans, which makes them at risk from the same diseases that we are, and it’s easy for them to catch them from us.

When tourists come in, they can bring a fatal flu, which is terrible, as it can wipe out the gorillas!

Also, the local community has to live with gorillas in their neighbourhood. The gorillas keep coming into their gardens to eat the banana plants or eucalyptus trees that they’ve planted – so they’re destroying the person’s livelihoods. People then put out dirty clothing and scarecrows to scare away gorillas and other wildlife, such as baboons.

The trouble with this is that gorillas are curious, so they touched the scarecrows and the dirty clothing. In the past, this lead to the first scabies outbreak among the gorillas, caused by mites, caught from the dirty clothes and scarecrows, burrowing under the skin of the gorillas.

How do you check the gorillas’ health, and whether they have any diseases?

We built a Gorilla health centre in Bwindi National Park, where we analyse gorilla poo regularly, especially when they’re sick. We also analyse samples from people and livestock, to see what they could be picking up from each other.

We train the park staff to monitor the health of the gorillas, and if there are any problems we advise or intervene if we need to.

We don’t always intervene though, because they’re wild animals. If they can recover on their own, we try to avoid human intervention so they don’t get weaker and end up depending on us. But if the problem is human-related, such as a suspected human disease, like the scabies, we have to intervene.

It’s a delicate balance of letting them get on with it, and helping them to survive as best they can.

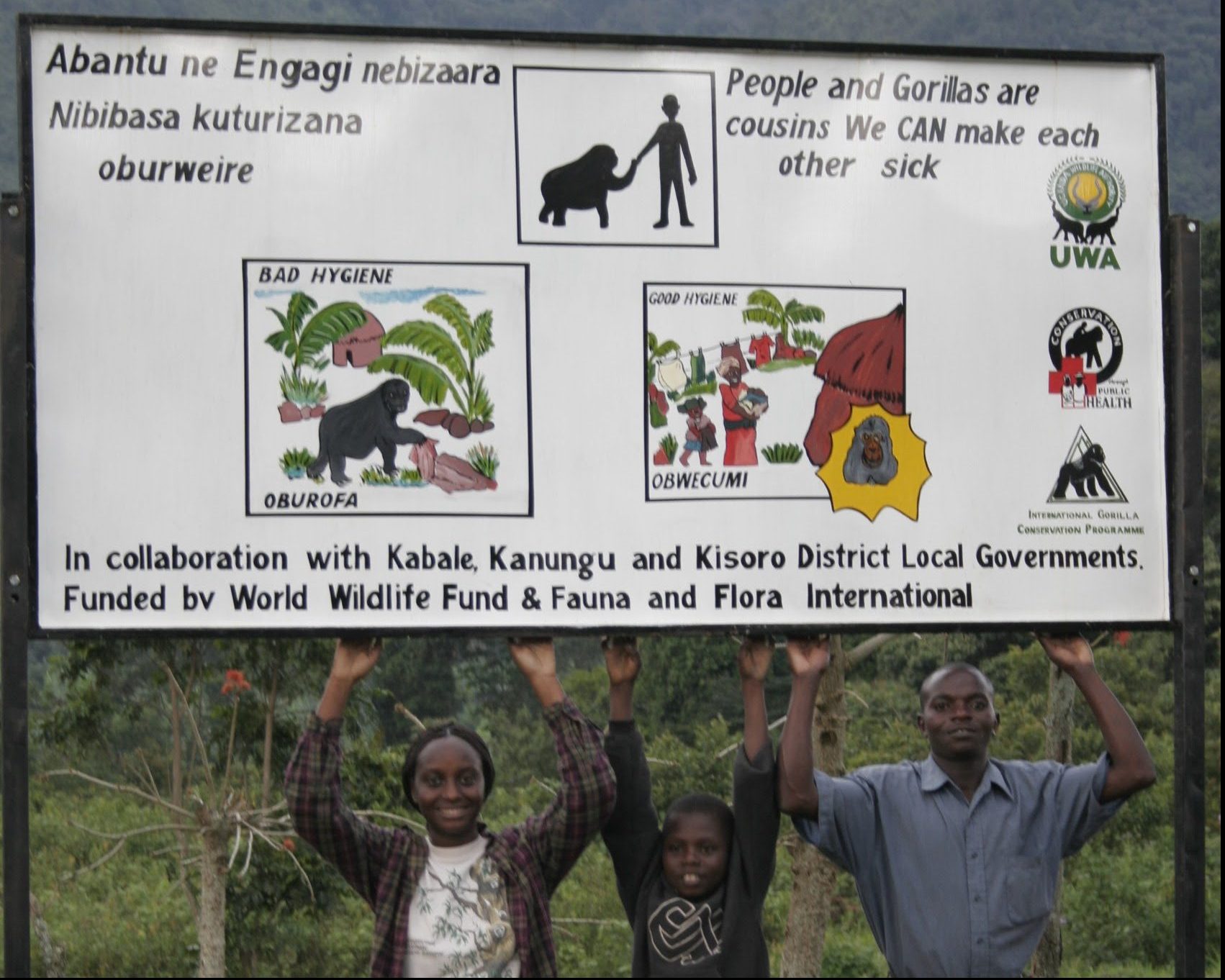

How do you help the local communities stop the spread of the diseases?

We help with education and setting up wash programmes. In Uganda there are a lot of infectious diseases due to poor hygiene, so we started up a ‘planned washing facility’ for people to be able to use proper washing facilities and hygienic toilets – as many people didn’t have access to proper toilets.

We also provide drying racks, so when people wash their dishes they don’t just put them on the ground to dry, where animals can go to the toilet on them, or where flies can get on them.

Providing clean drinking water from a protected water source and using clean water containers can make a huge difference, as well as teaching people to boil water before drinking it, to kill off any germs – so they don’t drink water that gives them diarrhea.

It sounds like your work is having a significant impact. So, you and I both believe strongly in the importance of educating future generations — you even set up your school’s Wildlife Club when you were growing up; was it common to have a wildlife club at school back then?

Wildlife Clubs were an initiative that originally started in Kenya. They were then taken up in Uganda in the 1970s, with the aim of trying to get all schools to have one of these clubs, to encourage children to care about local wildlife.

The school that I went to had previously had a wildlife club before I started, but it had been stopped. The Head-teacher was very strict, and after a school trip where the children misbehaved, he said: ‘No more wildlife clubs’.

But I kept going to one outside of the school, in the holidays. The people in the office there noticed how often I was going and told my biology teacher; “You have someone in your school, Gladys, who’s always coming here. She’s always stopping by the offices.”

So my biology teacher decided we needed to revive the wildlife club at our school, and asked me to set one up. I was so excited!

Does the school still have the Wildlife Club today?

Yes. We were able to win back the trust of the Headmaster, because we build a bird-feeding table for the school, held debating clubs and then went on school trip where no one misbehaved!

After I left, our school won the Miss Wildlife Competition – awarded to the people I trained and mentored – so he was very happy in the end. And today I’m actually the Chairperson of the Board of Wildlife Clubs of Uganda.

Amazing work! Last year, the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) declared the conservation status of mountain gorillas as ‘Endangered’, rather than the more severe risk of ‘Critically Endangered’. Was this a big success for the people working with gorillas?

I think it was too soon to say that. The mountain gorillas are found in two populations – Virunga mountain and Bwindi National Park.

The change to Endangered instead of Critically Endangered came from a census (population count) carried out in Virunga in 2016, that showed their numbers had recently increased to over 1,000. But we haven’t factored in the census in Bwindi, which my team are currently doing. What if we count the gorillas there and it’s less than 1,000?

The gorillas are still threatened by infectious disease, population growth, a small amount of poaching and habitat destruction. 1,000 is still very few and the threats to the gorillas mean they are still at high risk.

Learn more about gorilla conservation?

Want to know more about gorillas?

Post Comment